Why You Can't Compare Hillary Clinton's Age to Ronald Reagan's

Yes, she'd be the age he was upon taking office. But no, that's not relevant.

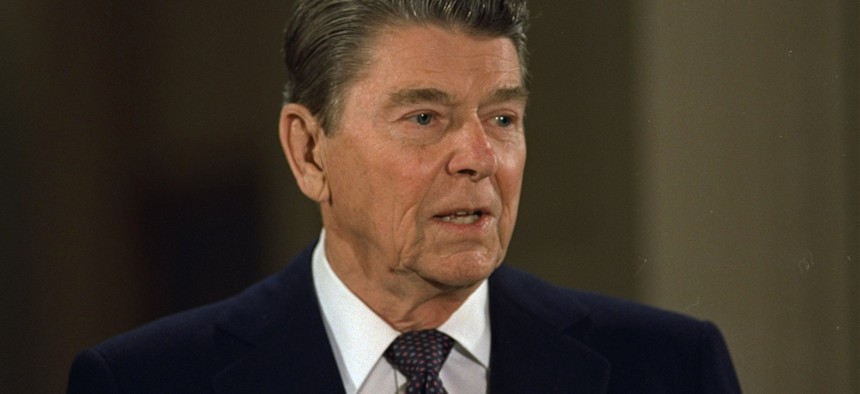

The age comparisons between Hillary Clinton and Ronald Reagan seem as natural as they are nonsensical.

Yes, were Clinton to win in 2016, she would take office at age 69—just as Reagan did in 1981. And yes, the comparison is often made when Clinton's critics and allies debate whether she has the health to serve out two presidential terms.

But it's a wildly misleading comparison, as the number that matters when assessing Clinton's health is not her age, but her life expectancy. And there is where the Clinton-Reagan comparison is revealed as a stretch.

A combination of federal data and a more nuanced approach to calculating Clinton's life expectancy—one that includes her gender, era, and other factors—projects the would-be president living to age 86. That means Clinton would live a full 17 years after taking office, more than enough time to serve out two terms.

Under the same criteria used to calculate Clinton's life expectancy, Reagan upon inauguration was projected to live to 81—12 projected years after taking the oath to Clinton's 17.

So, in terms of post-inauguration life expectancy, how does Clinton compare with other modern presidents?

Moving past the Reagan comparison reveals a complicated picture for Clinton. In terms of total life expectancy, were she to win in 2016, Clinton would take office with the longest projected total life expectancy of any president in the modern area.

But in terms of life expectancy after inauguration, Clinton's projected remaining years after taking office are dwarfed by total projected years forecast for our most recent presidents on their opening inauguration days: Barack Obama (32 projected years), George W. Bush (24.5 projected years), and Bill Clinton (30 projected years).

The best Hillary Clinton comparisons of life expectancy are to Richard Nixon (19 projected years after taking office), Gerald Ford (16 projected years), and George H.W. Bush (16 projected years)—all three of whom managed to take office without having to contend with concerns about their age.

Before Clinton's name entered the conversation, the most recent candidate to face age questions was 2008's unsuccessful Republican nominee, Sen. John McCain. Had he won, McCain would have taken office at 72 and was projected to live another 13 years—four fewer than Clinton.

So where do these projections come from?

For starters, the projections used the best available life-expectancy table from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Then, they factored in Clinton's gender, potential age at inauguration, and year of birth, as well as the fact that Clinton would be alive upon taking office (more on that last one later). Those same factors were used to project life expectancy for McCain and for every president from John F. Kennedy to Obama.

Why were those criteria selected?

Comparing Clinton's age at inauguration to the average American life expectancy is far from adequate. For one, as a female, she belongs to the gender that lives longer than men on average. That fact is at times noted in the general discourse over her age, but there's more to it than that.

Clinton's projection is made more precise by factoring in her year of birth: 1947. Her birth year matters because a person born in 1947 will average a longer life than one born earlier and a shorter life than someone born later—in large part due to the ongoing improvement in health and medical knowledge.

The calculation includes one more wrinkle. It factors in that Clinton would—upon taking office—still be alive at 69. That seems trivial, but it matters because the longer one lives, the longer one is projected to live. As a person ages, her average life expectancy grows, in part because it no longer includes those members of their cohort who have already passed away.

What was left out?

The above yields a better projection than most—and certainly a superior comparison than just listing ages—but it remain a simplified version of the ideal.

Clinton's, or any other president's, projection could be improved by including ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and lifestyle. There's no limit to how deep into the data one can drill, and the more factors included, the more sophisticated and specific the model—all the way down to a data profile that would capture almost every aspect of Clinton's life and lifestyle.

But what is more useful in predicting longevity than any demographic data, however, is personal health history.

And that's where Reagan again becomes relevant to the conversation. The former president demonstrated the fallibility of life expectancy projections by surviving to age 93, and he revealed age to be too narrow a metric for assessing a candidate's health: Reagan's final years were spent living with Alzheimer's.

So when it comes to Clinton, the best place to learn about her life expectancy is likely not her statistical data, but her doctor's office.