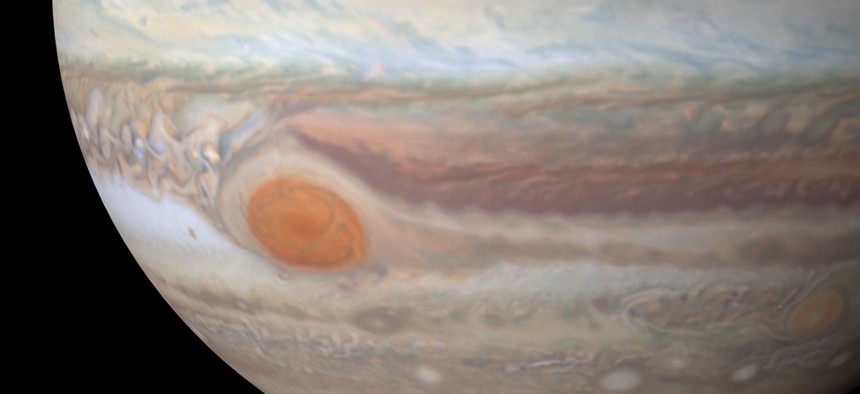

Solving the Mystery of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot

When NASA’s Juno probe reaches the planet in July, scientists may finally find out what drives the strange phenomenon.

The Great Red Spot wasn’t always red.

Early observers said the oval swirl, Jupiter’s most puzzling and distinctive marking, was more of a salmon pink—or even pale violet—before darkening to a brick red in the early 1880s. After that, it seemed on the brink of vanishing for a time, before it swelled and again deepened in hue. Today it is again shrinking, and it’s turning orange.

No one is sure why, but we may soon find out. NASA’s Juno mission is currently on the way to Jupiter, where it will take an unprecedented close-up of the Great Red Spot.

“We’re going to skim within 3,100 miles of Jupiter’s cloud tops—in between the cloud tops and just inside the most intense portion of the radiation belt,” said Rick Nybakken, Juno’s project manager. “Nobody’s ever ventured there before. No spacecraft has ever operated this close to Jupiter.”

People have been captivated by the planet’s spot for centuries. Scientists today know that the Great Red Spot is an anti-cyclonic storm, a hurricane-like high pressure system that’s three times the size of Earth and has been raging for 400 years—maybe longer. (Its nickname seems to date back only to the 1870s, however.) The chaotic storm has churned for so long, astronomers surmise, because it has never made landfall—there is, after all, no land to fall upon.

The fact that the spot is actually a storm swirling in the Jovian atmosphere helps explain one of the characteristics that astronomers a century ago found most troubling. The Great Red Spot didn’t exactly stay put; it seemed detached from the planet’s surface. “No observer understands the cause of this huge rift,” The New York Times reported in 1880. “It may be an opening in the cloud-atmosphere disclosing the more solid matter beneath, and it may be something beyond human ken.”

In the late 19th-century and early 20th-century, observers of the night sky developed several theories as to why the spot appeared this way. Perhaps it was a cooling portion of planetary crust on an otherwise gaseous body, an “enormous piece of slag, floating on the molten planet,” as the Philadelphia Record put it in 1902. In other words, it was a newborn continent. Or maybe it was a region of Jupiter that was, for some reason, hotter than the rest of the planet, not cooler—and it was heat that dissipated into the distinctive patch of red clouds that looked odd and spotlight to space enthusiasts on Earth. Scientists flirted with the idea that the spot was actually an opening in the cloud cover that otherwise enveloped Jupiter, an elliptical red glimpse at the planet below.

Others surmised the spot was the product of “solar attraction,” a phenomenon caused by the sun. Some believed it was evidence of a new satellite in the making, a “Jovian moon in embryo,” according to The Washington Herald in 1915. And as recently as the 1950s, at least one observer claimed to have seen snow-capped mountains on the spot—as though it were a Laputa-esque island, floating in the clouds.

A story about Jupiter’s Great Red Spot in The Washington Times, November 1921 (Library of Congress)

Misguided though these early ideas may have been, the great red spot did help scientists piece together some key information about the monstrous planet. It was, for instance, instrumental in giving astronomers a measure of Jupiter’s rotation. And it informed the understanding that the planet was, in fact, a giant ball of gas. Or, as the Omaha Daily Bee put it in 1916, a planet in “a constant state of ebullition, like a boiling globe where nothing retains a permanent shape, except, perhaps, the strange region called ‘the great red spot.’” (For the record, Jupiter may be something of a shape-shifter, but it’s actually frigid for the most part.)

In the first photographs ever taken of Jupiter, the great red spot was visible, but not clearly so. In one famous photograph, circulated by the Associated Press and published by The New York Times in 1952, the spot is beneath the circular shadow in the upper left portion of the planet—that shadow is cast by one of Jupiter’s dozens of moons.

At times, the spot has appeared to have companions. In the 1930s, observers noticed “one very dark belt” just below the great red spot, but it soon dematerialized. Today, as the spot appears to be shrinking and fading to orange, people remain charmed by it. Many of the planetary scientists working on the Juno mission, which it set to enter Jupiter’s orbit on July 4, are fixated on the spot.

“It’s even more interesting nowadays as we realize it’s shrinking,” said Scott Bolton, Juno’s principal investigator. “It’s lasted for hundreds of years and now we’re starting to see it’s getting smaller, so we’re getting there at a very exciting time.”

An artist’s rendering of what Jupiter might look like from the surface of Europa. (NASA / JPL-Caltech)

Observers have long tracked the great red spot’s surface area—it spans longer than 10,000 miles across the mammoth planet—in Earth terms, about the distance from New York City to Melbourne, Australia. Now, Bolton and other scientists believe Juno may be able to tell them how deep the spot is. “Are the roots deep? Is it bigger underneath or smaller underneath? It’s very exciting,” Bolton told me. He and his colleagues are also hopeful that new data from Juno will contribute to their understanding of what’s fueling the gargantuan storm.

“What we’re seeing now is just the part that pokes through the clouds,” said Steven Levin, a project scientist on the mission. “We have a general idea of where its energy comes from to drive the storm—Jupiter is rotating really fast and it has heat leaking out from the inside—but we don’t understand the dynamics too well.”

If all goes as planned, scientists will have reams of data about Jupiter by the end of August, and even more in the months that follow. That data will include new information about the planet’s gravity and magnetic field, details that could help tell the story of Jupiter’s formation, and illuminate the forces that stir the great red spot. “The truth is,” Levin told me. “I’m sure that the most exciting result will be something we haven’t even thought of, when we get some sort of surprise from Jupiter.”

Jupiter, meanwhile, keeps furiously spinning, its most distinctive marking still fading in and out of view. “This beautiful planet,” as the Times wrote of Jupiter in 1880, “serenely unconscious of the excitement induced by his movements.”