Intel Chiefs Dodge Questions on Alleged Trump Interference in Russia Investigation

They felt comfortable saying they hadn’t felt pressure from administration officials to influence the probe. But they declined to answer direct queries from senators about their interactions with the president.

In a series of at times tense exchanges on Wednesday, top U.S. intelligence officials repeatedly declined or evaded questions from lawmakers on the Senate Intelligence Committee about their interactions with President Trump and whether the administration ever directed them to intervene in the ongoing federal Russia investigations.

Instead, senior administration officials offered up a blanket, albeit vague, defense of the administration. National Security Agency Director Michael Rogers insisted that he has “never been directed to do anything I believe to be illegal, immoral, unethical, or inappropriate,” and does not remember feeling “pressured to do so.” Director of National Intelligence Daniel Coats told the panel that he has “never been pressured—I've never felt pressure to intervene or interfere in any way with shaping intelligence in a political way or in relationship to an ongoing investigation,” referring to his interactions with the president or other administration officials.

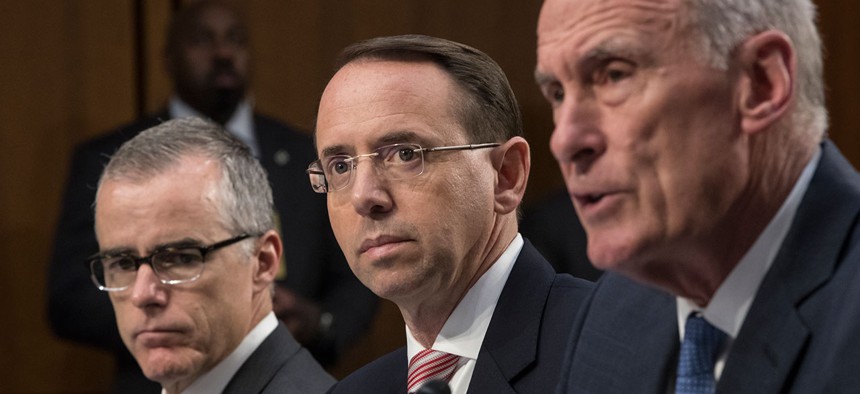

Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein and Acting FBI Director Andrew McCabe also testified during the hearing. Democratic lawmakers, as well as some Republicans, made it clear from the outset that Trump and the Russia probes would dominate much of their questioning—not the session’s original focus, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which authorizes the government to spy on U.S. citizens in select circumstances.

Many of those queries centered on recent media reports. On Tuesday night, The Washington Post reported that Trump asked Coats in March if the director could compel Comey to ease up on the FBI’s inquiry into former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn. Coats reportedly decided it “would be inappropriate” for him to do so, according to unnamed officials. That story followed another from the Post, published in May, asserting that Trump had previously asked both Coats and Rogers to publicly refute the possibility of collusion with Russia during the presidential election.

While the witnesses felt comfortable saying they hadn’t felt pressured to intervene in an investigation, they declined to answer direct questions about whether the alleged questions or requests had ever come up. At one point, Florida Senator Marco Rubio asked if Coats was “prepared to say that you have never felt—never been asked by the president or the White House to influence an ongoing investigation?”

“I am willing to come before the committee and tell you what I know and what I don’t know,” Coats replied. “What I’m not willing to do is to share what I think is confidential information that ought to be protected in an open hearing, and so I’m not prepared to answer your question today.”

“Director Coats, with the incredible respect I have for you, I am not asking for classified information,” Rubio said. “I am asking whether or not you have ever been asked by anyone to influence an ongoing investigation.”

“I understand, but I'm not going to go down that road in a public forum,” Coats replied. “And I also was asked the question if the special prosecutor called upon me to meet with him to ask his questions, I said I would be willing to do that.”

During an exchange with Republican Senator John McCain, Coats again emphasized his unwillingness to discuss specifics, but suggested he could speak more freely in a closed, or private, session with the panel.

“I would hope we’d have the opportunity to do that,” he said. Coats “did not want to publicly share what I thought were private conversations with the president of the United States—most, if not all of them, intelligence-related and classified,” he explained. “I didn’t think it was appropriate for the Post to report what it reported or to do that in an open session.”

The officials’ efforts to avoid answering questions grated on some of the Democratic lawmakers, as well as on Independent Senator Angus King of Maine, who excoriated Coats and Rogers for not being more forthcoming. When King tried to extract an answer from the NSA director, Rogers replied: “It's not appropriate in an open forum to discuss those classified conversations.”

“What is classified about a conversation involving whether or not you should intervene in the FBI investigation?” King countered. “I stand by my previous comments,” Rogers replied.

His questions to Coats fared little better. Part of the dispute revolved around whether officials were refusing to answer because of executive privilege, which the White House has ruled out invoking for Thursday’s hearing with former FBI Director James Comey. Since the Kennedy administration, presidents have typically asserted their power at their own personal discretion, making it unclear whether it could or did apply during Wednesday’s hearing. The officials themselves offered little clarity.

“You swore that oath to tell us the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, and today you are refusing to do so,” King told Coats. “What is the legal basis for your refusal to testify to this committee?”

Coats paused for a moment before answering. “I’m not sure I have a legal basis, but I’m more than willing to sit before this committee during its investigative process in a closed session and answer your question,” he replied.

The hearing began exactly 24 hours before Comey’s highly anticipated testimony; the ex-FBI chief, who the president abruptly fired in May, will appear before the same Senate committee.