China Has a ‘Space Force.’ What Are Its Lessons for the Pentagon?

Space is an increasingly important arena for the U.S.-China strategic rivalry.

The Chinese military seems to agree that the current U.S. approach to space is hindered by some serious shortcomings.

If the United States is to maintain military advantage in space, as President Trump has promised – and as his new Space Force is meant to do – U.S. policy and strategic decisions should be informed by an understanding of China’s ambitions to become an “aerospace superpower” (航天强国) – and how the Chinese military has reorganized itself to seek dominance in space (制天权).

Start with the way space is characterized in China’s military strategy: the “new commanding heights in strategic competition.” Once a sanctuary for U.S. satellites that have fostered unparalleled military capability, space is now recognized by Chinese military strategists as a critical U.S. vulnerability. Without reliable space support, U.S. capabilities for global C4ISR and precision strike will fail, and the U.S. military could be reduced to a level of merely mechanized warfare, by the assessment of one Chinese defense academic.

This recognition has motivated the development of a range of “trump card” weapons (杀手锏). Some, like various cyber or electronic warfare attacks, could remain plausibly deniable in a crisis or conflict. But the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has also been developing direct-ascent and co-orbital kinetic kill capabilities that could be directly damaging. These include the DN-2 ASAT missile, whose 2013 test first demonstrated a potential capability to target U.S. satellites in geosynchronous orbit, and the DN-3 hit-to-kill midcourse interceptor, tested successfully as recently as February 2018.

At the same time, China is also rapidly expanding its own architecture of space systems, which will increase its military capabilities but also create new potential vulnerabilities. So far in in 2018, China has undertaken a record 25 launches successfully. China is on track to create “a global, 24-hour, all-weather earth remote sensing system” by 2020, including satellites with EO, SAR, and ELINT payloads. BeiDou, China’s indigenous competitor to GPS, is expanding from a regional capability to a system with global reach. China has even launched the world’s first quantum satellite and plans to launch constellations of micro- and nano- quantum satellites in the years to come in order to expand its quantum communications infrastructure – and perhaps set the stage for a future ‘quantum Internet.’

The PLA recognizes the importance of space-based information support to enable joint operations and expand power projection. This prioritization was shown by the 2015 establishment of the Strategic Support Force (PLASSF, 战略支援部队), which has integrated PLA space, cyber, and electronic warfare capabilities. This reflects a unique innovation in force structure – and a paradigm that PLA thinkers believe could be superior to the current U.S. approach.

In particular, the PLASSF will be integral to enabling the integration of the PLA’s system of systems (体系) that will undergird its joint operations. Its commander, Gen. Gao Jin (高津), has emphasized the PLASSF will provide a vital ‘information umbrella’ (信息伞) for the whole military’s system of systems, recognizing this as a “key force for victory in war.” Xi Jinping himself has declared that the Strategic Support Force will be “an important growth point for our military’s new-quality combat capabilities.”

Indeed, the Strategic Support Force’s design and structure are meant to enable the integrated development of the battle networks that are critical to today’s “informatized” (信息化) warfare. In particular, the PLASSF is intended to enable the “information chain” that connects the initial intelligence, reconnaissance, and early warning capabilities with information transmission, processing, and distribution, and then, after an attack on an adversary, with the options for guidance, damage assessment, and follow-on strikes.

The PLA’s focus on the criticality of C4ISR has been informed by close study of U.S. ways of warfare, and the structure of the PLASSF is designed to be superior to the U.S. model. The current U.S. approach is seen as hindered by the lack of integration, coordination, and resourcing, as well as certain redundancies, in its own space systems and support capabilities, by the characterization of a Chinese military expert.

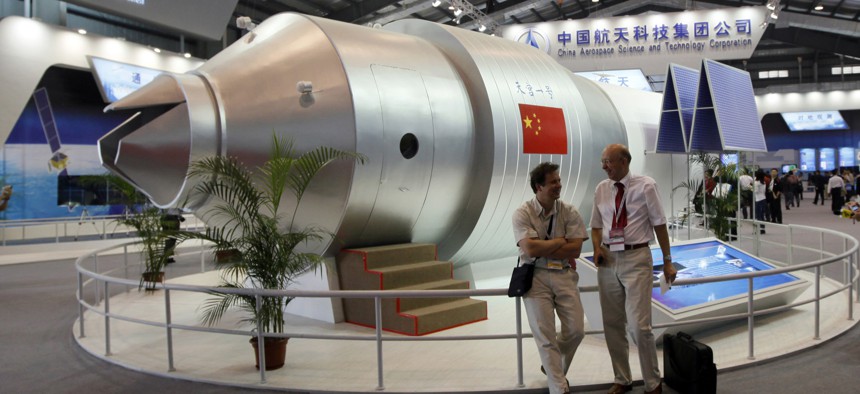

By contrast, the PLASSF’s Space Systems Department (航天系统部), evidently a de facto ‘Space Force’ for the Chinese military, has consolidated control over a critical mass of China’s space-based and space-related capabilities. The establishment of a unified structure through the Space Systems Department seems to reflect a response to organizational challenges that resulted from the prior dispersal of these forces, systems, and authorities across the former General Armament Department and General Staff Department.

Within the PLA, debates about whether to build a space force date back to the mid-2000s; both the PLA Air Force and Rocket Force appeared to seek the lead in this new domain. For instance, in 2009, then-PLA Air Force Commander Xu Qiliang had argued for the creation of a space force in response to increasing competition in space. In certain respects, its structure may thus reflect an organizational compromise, creating a new structure that centralized the control of these strategic capabilities directly under the Central Military Commission.

If successful, the Strategic Support Force will serve as an “important support brace” for future PLA joint operations. The PLASSF is intended to create “historic levels of data fusion and timely sharing of information,” increasing the “enjoyment” of these support resources throughout the military, including through enabling more effective integration of information and intelligence.

This system of systems will be ever more vital as the PLA looks to enhance its capability to project power beyond the first island chain. This greater leveraging of space does creates a higher degree of dependence and thus potential vulnerability for the PLA. However, in likely conflict scenarios in the Indo-Pacific, there would likely be major asymmetries in vulnerability between the U.S. and China, since the U.S. would be more reliant upon space to project power, whereas the PLA could possess more alternatives to compensate for a potential disruption of space-enabled capabilities, including the use of UAVs for ISR or data relay at a local level.

Looking ahead, Chinese military strategists also recognize that space deterrence will integral to the PLA’s posture for strategic deterrence and critical to achieving an advantage in a crisis or conflict scenario. PLA strategists have argued, “Whoever is the strongman of military space will be the ruler of the battlefield; whoever has the advantage of space has the power of the initiative...” Some PLA thinkers anticipate the first blow in any future war will likely be struck in space. The Strategic Support Force, which will likely have responsibility for certain PLA counterspace capabilities, particularly options for cyber attacks and electronic warfare, could thus serve the tip of the spear for Chinese military power.

The U.S. Response

As the U.S. considers new options to optimize its own force posture in anticipation of the future operational environment, the Chinese military’s new paradigm for space should be taken into account. The PLA has chosen to integrate and consolidate a critical mass of authorities and capabilities for space within a single organization. This approach may have certain advantages, including likely greater resources, centralized development and employment of space systems, and dedicated approach to personnel and training. Of note, the PLASSF Space Systems Department oversees the Space Engineering University, which will train and educate students in specialties ranging from command information systems to remote sensing technologies, while perhaps developing the PLA’s future space leaders and war-fighters through its Space Command Academy. However, this new structure may not resolve prior bureaucratic shortcomings in the PLA, and the PLASSF’s ongoing process of force development could be lengthy and challenging.

For the U.S., there are similarly compelling rationales to recognize the criticality of space and accelerate efforts to ensure the resilience of our space-enabled C4ISR architecture. The question of whether a corps, combatant command, or new military service would be the most appropriate organization will require more extensive consideration, which is beyond the scope of this piece. However, it is clear that the U.S. military must explore new options to leverage commercial innovation, while also concentrating on alternatives to bolster options for C4ISR beyond space, as my CNAS colleagues Adam Routh and Paul Scharre have argued respectively.

PLA strategists seem to believe that the U.S. can’t or wouldn’t fight without its satellites. For the U.S., to bolster deterrence in the Indo-Pacific will require proving that prediction wrong. At the same time, the PLA’s own growing reliance on its space systems will create new vulnerabilities. However, the Chinese military may remain better postured with alternatives to sustain C4ISR capabilities, since the U.S. would confront the challenges of power projection, while the PLA would be playing a ‘home game’ in likely conflict scenarios. While Sino-U.S. security dilemmas and strategic competition play out in this new ‘high ground’ of military power, it will also be critical to explore the implications of this rivalry and contention in space for future strategic stability, given the risks of misperception and unintended escalation.

NEXT STORY: Trump Calls Out Election Meddling—By China