The Tiny Trump Budget Cut That Could Blind America to the Next Zika

The Obamacare repeal would halve a little-known fund that’s vital for monitoring unexpected infectious threats.

The science community is still reeling from the huge cuts proposed by President Trump’s budget blueprint. If it passes would slash $5.8 billion from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), $2.5 billion from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), $900 million from the Office of Science at the Department of Energy, and $250 million from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). If Congress approves the budget, it would “set off a lost generation of American science,” as my colleague Adrienne LaFrance reported.

But with the budget threatening to carve large gaping gashes into the flank of American science, it’s easy to lose sight of the damage that even small nicks can inflict.

Consider the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity (ELC) program. It’s a little-known, unglamorous, and modest fund. But it’s also vital for America’s ability to respond to infectious diseases, and especially to unforeseen emergencies like Ebola, Zika, or whatever else is coming next. If the Republican plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act goes ahead, the ELC’s budget will be cut in half. That’s a loss of $40 million—just 0.7 percent of the cut that’s planned for the NIH. But it alone would leave the U.S sluggish and myopic when it comes to infectious diseases.

“It’s going to take us longer to discover that people are becoming ill, longer to realize the connection between them, and longer to figure out how to treat them,” says Peter Kyriacopoulos, senior director of public policy at the Association of Public Health Laboratories. “We’ll have more people sick.”

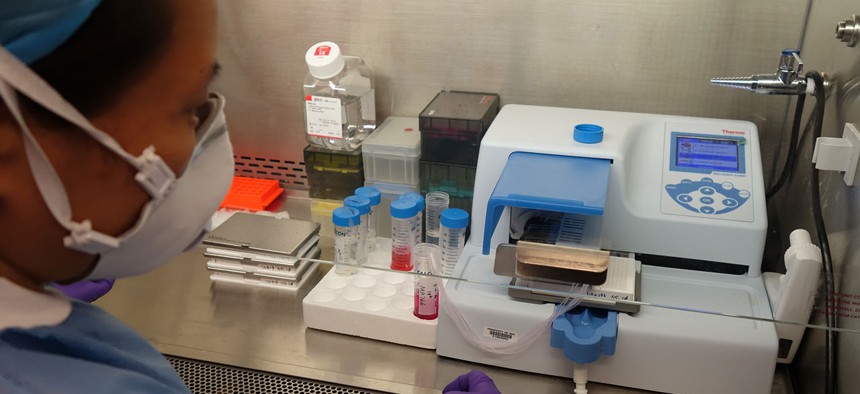

Every U.S. state has at least one public health laboratory, whose job it is to monitor for infectious diseases and other health threats. These facilities are the local eyes and ears of federal agencies like the Centers for Disease Control. On any given day, they might test blood samples for Zika, captured bats for rabies, water for harmful algae, mysterious powder for bioterror threats, newborn babies for genetic disorders, milk or meat for foodborne diseases. They look at which flu strains are sweeping the country, which drug-resistant microbes are rearing their heads, which new diseases are invading American shores. When Ebola arrived in Dallas in September 2014, it was the Texas state public health lab that confirmed its presence by testing a patient’s blood for the virus.

Created in 1995, the ELC program gives the public health laboratories funds for training their staff and buying equipment. It’s not sexy, but it is essential. And until recently, it was relatively small—between 2004 and 2008, it doled out $50-60 million a year, across all 50 states.

“Public health is never well-funded, which means that in the lab, things get very, very tight,” says Kyriacopoulos. “I often say that in this country, we’re lucky we don’t have more than one public health emergency at a time. If we had Zika and a serious foodborne disease outbreak, we would have been in very bad shape.”

The program’s fortunes changed in 2010, when the Affordable Care Act was passed. The act’s Prevention and Public Health Fund (PPHF) infused an extra $40 million into the ELC, almost doubling its budget. Better still, those funds were flexible. Until then, most ELC money was tied to specific diseases, grouped into a few dozen categories. You couldn’t use, say, flu money for tick-borne diseases, or prion money for fungal infections. The new funds came with no such restrictions.

“It gives me the flexibility to do whatever I need to do and to build capacity for what we don’t know about already—like Zika,” says Sara Vetter, who manages the Infectious Disease Lab at Minnesota’s Public Health Laboratory. When the Zika epidemic hit last year, it took seven months for Congress to approve extra funds to fight the disease. In the meantime, Vetter used ELC money to buy everything she needed to start testing for the virus. Without it, thousands of samples would have arrived at the labs and gathered dust. Thousands of women would have waited months for answers.

Similarly, the people who were hired using the extra ELC money weren’t tied to one particular disease, but could be cross-trained to deal with any of them. The funds literally bought flexibility. Some states used them to deal with Zika, while others expanded testing for re-emerging diseases like measles and mumps. They paid for electronic systems for sharing data, and courier services to safely transport hazardous specimens between facilities. “They allow you to perform constant surveillance in the community and identify when you need to respond,” says Kelly Wroblewski, Director of Infectious Disease Programs at the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

That will change, if the GOP’s plans come to fruition. The bill that repeals and replaces Obamacare will eliminate the PPHF entirely, which would bring the ELC back down to its previous cash-strapped level and remove those vital cross-cutting funds. And with the CDC standing to lose 12 percent of its own funding, it isn’t clear whether the lost money could be replaced.

The impact of that loss wouldn’t be immediately felt: the public health laboratories still have Ebola and Zika money in their coffers. But those are temporary boons. When they run out, “we would need to make tough decisions,” says Vetter. “If a new public health threat hits, do we stop another type of testing to respond to it? Do we put rabies testing on hold? Or food-borne illnesses?”

As I reported before, the Trump administration's policy approach could leave the U.S. vulnerable to a future pandemic. And right now, H7N9 bird flu is rearing its head in China. The country is going through its fifth epidemic since 2013. This one has led to far more human infections—460, as of late February—than the previous four, and the viruses have new mutations that may make them more dangerous. Most infected people have experienced severe illness, and there are signs of limited spread from person to person. The virus has already reached the U.S., and caused outbreaks among the birds of two Tennessee farms. If H7N9 becomes a more significant problem, and especially in areas where Zika is still prevalent, many public health labs will likely have to choose which to deal with.

“I’m very concerned about our ability to respond to H7N9 bird flu or anything else that’s emerging,” says Vetter.

NEXT STORY: Some Agencies On Trump’s Kill List Push Back