Spirit met its end in 2009. While exploring, the rover broke through some crustand slipped into a sand pit. Engineers commanded the rover to wiggle its wheels, but it was stuck. For the first time in its mission, Spirit wouldn’t be able to drive to a north-facing slope. The rovers looked for these slopes each winter, where their solar arrays could absorb as much sunlight as possible each day. “We saw it coming,” Steve Squyres, the principal investigator for both rovers, told me. “I knew from day one, if Spirit has to spend a winter on flat ground, that was going to be Spirit’s last winter.”

NASA Declares a Beloved Mars Mission Over

The space agency will stop trying to contact the Opportunity rover, which was sent to Mars to search for evidence of water.

The Mars probe came barreling in. It streaked through the planet’s atmosphere at about 12,000 miles per hour. With the surface in sight, its parachute unfurled. The probe fired its rockets to slow itself down, and inflated its airbags to cushion the landing. Touching down gently, it bounced across the clay-colored terrain.

When the dust settled, the probe unwound itself, like a flower opening toward the sun, and revealed its cargo: a rover, no bigger than a golf cart.

The rover, named Opportunity, was sent to study what the Martian surface was made of. If there had ever been life on this other planet, the composition of the alien dust, soil, and rock might hint at its nature. The rover’s work was slow and precise. For years, it rolled over plains and craters, digging into the ground and relaying its findings to Earth.

Then, last summer, it stopped. On Tuesday, following months of attempts to regain contact, the Opportunity team sent a final set of commands to the rover. After receiving no response, NASA declared that the Opportunity mission, after nearly 15 years, is officially over.

“I was there with the team, as the commands went out into the deep sky. And I learned this morning that we had not heard back,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s science division, in a press conference. “It is therefore that I’m standing here with a sense of deep appreciation and gratitude that I declare the Opportunity mission as complete.”

In June 2018, an enormous dust storm clogged the Martian atmosphere, blocking sunlight from reaching the surface. Opportunity, a solar-powered rover, couldn’t charge its batteries in the darkness and entered a deep sleep.

Engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory made more than 1,000 attempts to rouse Opportunity. The rover did not respond, even as the storm passed in September. The team held out for a windy season in January, which could wipe off any dust coating the rover’s solar panels. They ran out of options. Engineers transmitted a final set of commands to Opportunity on Tuesday night—one last chance—and received nothing but silence in return.

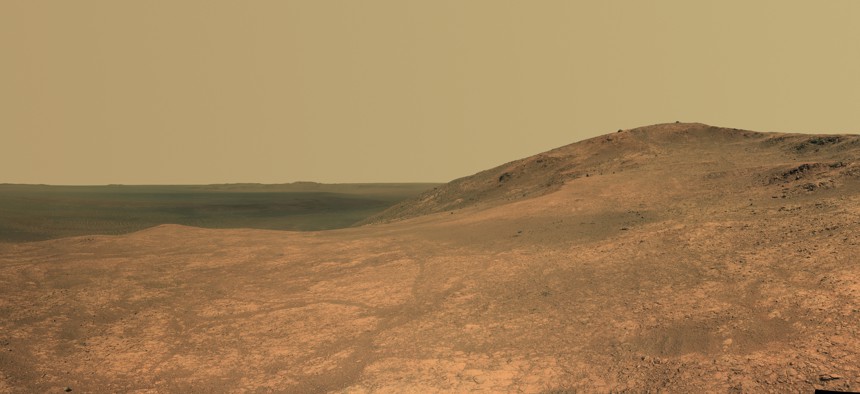

During its years on Mars, Opportunity crept along at a tiny fraction of a mile per hour. A robotic arm burrowed into the surface, exposing fresh rock, and scooped soil samples for analysis. Scientists back on Earth delighted as Opportunity returned detailed images of the landscape, and when the rover found evidence that Mars once had water, enough to support microbial life.

The engineers sent the commands, directing the rover where to drive and what to inspect, but it seemed, at times, as if Opportunity was doing the work on its own. The rover’s communication with mission control felt less like data transmissions from a mindless robot, and more like dispatches from a curious explorer.

The end of Opportunity leaves only one functioning rover on Mars: Curiosity. Curiosity arrived on the planet in 2012 and, despite some technical problems of its own last year, is in good health. The rover is on the opposite side of the planet, and with Opportunity shut down, “we basically lost our surface presence on one half of Mars,” says Mike Seibert, a former Opportunity flight director. (Seibert was around for the last massive dust storm on Mars, in 2007, which the rover survived just fine.)

Curiosity doesn’t have the time or speed to trundle over and check on its friend. The only views NASA has of Opportunity come from robotic spacecraft that orbit Mars, like satellites circle the Earth. From here, Opportunity is a fuzzy smudge against a vast, rugged landscape.

For engineers and scientists, the pain of the mission’s demise is softened by this fact: Opportunity was supposed to die years ago. Opportunity was one of two rovers NASA landed on Mars in 2004. The other, named Spirit, touched down on the other side of the planet. The missions were expected to last three months, but they kept going for years.